Speed kills

The Extraordinary Story of Pioneering Aviator Amy Johnson

Johnson became a living legend; her achievements feted nationally and internationally.

But her life was cut short in 1941 when, aged just 37, her plane plunged into the Thames Estuary under contentious circumstances.

Here is her extraordinary story.

Amy Johnson was born in Hull, 1 July 1903. Her father John was a partner in the family fish-processing business. Johnson was smart, rebellious and, after university, moved to London and took on a series of jobs, becoming a legal secretary.

For an unknown reason, in spring 1928, she visited Stag Lane Aerodrome in London’s Edgware, home of the London Aeroplane Club. She quickly became a member – her expensive fees paid for by her supportive father – took her first flying lesson in September 1928 and, after 19 hours flying, was awarded her pilot’s licence, July 1929.

This was a radical move at that time but, perhaps even more unusual, was her learning how to maintain an aircraft – taught by the club’s Chief Mechanic, Jack Humphreys – gaining her Ground Engineer’s licence 5 months later. Humphreys said she was a ‘born engineer.’

Amy was a very inexperienced pilot – the longest flight she had attempted was the 180 miles from Stag Lane Aerodrome to Hedon Aerodrome, Hull. Yet she had an iron resolve to fly 11,000 miles and break Australian Bert Hinkler’s speed record. He flew solo from from England to Australia in 1928, taking 15.5 days.

Amy pursued a long campaign to raise funds for her epic flight, finally getting the financial backing and support of the Castrol oil magnate, Lord Charles Wakefield. Her father also gave her money. She bought Jason, her second-hand Gipsy Moth bi-plane (now housed in London’s Science Museum), for £600 and secured petrol and oil supplies along her route.

Amy navigated using only a compass, plus basic maps with a ruler to plot the most direct routes. She had no radio link to the ground and no reliable information about weather conditions.

During the epic flight she narrowly missed flying into a mountain range, endured a forced landing in a desert sandstorm, another in a jungle among what she initially thought was a hostile tribe, flew through tropical storms and was caught up in shock waves from a volcanic eruption.

Amy battled engine problems, heavy landings, fear of flying over open water, fierce head winds, exhaustion, loneliness, extreme cold in the open cockpit where she flew for up to 12 hours a day, as well as realising halfway through the flight that she would not be able to beat Bert Hinkler’s record.

But, wherever she landed, there were enthusiastic local crowds to greet her, growing enormously in number as word of her journey spread.

Throughout Amy’s 20-day flight, her father and family sent her encouraging cables, always stressing safety over speed.

Hero’s welcome, publicity tours and a crash

Hero’s welcome, publicity tours and a crashAmy had landed at Darwin, Australia, 24 May 1930, to a hero’s welcome. She had become a worldwide celebrity.

Congratulatory telegrams poured in, including from King George V and Queen Mary, and from British Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald. She was showered with gifts and fan mail. Songs were written about her. She was later awarded a CBE. The British press dubbed her ‘Queen of the Air.’

Amy’s publicity tour was a gruelling round of speeches, receptions and parades. With no time to rest, she was exhausted and crashed at Brisbane’s aerodrome in front of hundreds of spectators. Jason was virtually destroyed. She suffered only bumps and bruises.

The plan had been for her to fly round Australia in her plane. Now she had to be ferried as a passenger for the rest of her tour, including being piloted by the Scot, Jim Mollison, a rising aviation pioneer who was later to become her husband.

Amy returned to England on 4 August 1930. Huge crowds greeted her arrival. In London – more than one million people lined the parade route as she was driven through the streets in an open-topped car. Over 300,000 people welcomed her back to Hull, her home city.

The ‘Daily Mail’ had bought her story and paid her £10,000. This sponsorship deal was on the understanding that she would undertake a 3 month publicity tour of Britain. However, after a month of exhausting public appearances, she collapsed. The tour was abandoned and she temporarily retired from public view.

Amy soon returned to flying, cementing her fame with more records. In July/August 1931, she and her old engineering instructor, Jack Humphreys, made a record-breaking 10-day flight from London to Japan in a Puss Moth named ‘Jason II’. Amy broke flight records again, flying solo to Cape Town, South Africa, in 1932 and regaining this record in 1936.

She married Jim Mollison in 1932. He had set flight records himself, including the first solo crossinAmy Johnson (left) and Amelia Earhart in New York, 2 August 1933. Amelia was America’s ‘first lady of the air’, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. She disappeared in mysterious circumstances while flying over the Pacific Ocean in 1937. Source: The Amy Johnson Estate.

However, their plane crashed in Bridgeport, Connecticut, short of their target. Amy and Jim were both injured. He was hospitalised. Despite this, they achieved the record and were given a huge ticker-tape welcome in New York, where they were entertained by President Franklyn Roosevelt, and met and became friendly with Amelia Earhart.

Amy and Jim’s tempestuous marriage, conducted in the full glare of publicity, faltered over the years. They divorced in 1938.

g of the Atlantic. They were a world-famous glamorous celebrity couple – the ‘flying sweethearts – often flying together on highly publicised trips, including attempting a long distance record by flying from Pendine Sands, Wales, across the Atlantic to New York.

Amy became aviation editor for the ‘Daily Mail’ in 1934. She was a commercial pilot for a short time in 1934 and 1939. She appeared in ‘Vogue’ magazine in 1936, modelling a collection of flight wear designed for her solo flight from London to Cape Town by the leading Italian fashion designer, Elsa Schiaparelli. She took up motor rallying and gliding. She drove fast cars.

But the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 made her reconsider her very public life.

The civilian ATA took over all the ferrying of military aircraft from factories to RAF airfields during the war, as well as the ferrying between airfields. 188 of the 1,245 pilots were women. Pilots flew a range of aircraft, from bi-planes to Spitfires and heavy Lancaster bombers.

They flew the unarmed aircraft within sight of land below; they were not taught how to fly with instruments. They had no navigational aids or radios, just maps and a compass. They flew blind in all weathers.

Amy Johnson was perfectly qualified, joining up in May 1940.

On 5 January 1941, snowy, freezing cold and foggy, Amy took off in a twin-engine Airspeed Oxford plane on a routine 90 minute flight from Blackpool Aerodrome to RAF Kidlington near Oxford. Four hours later she parachuted into the Thames Estuary, many miles off course. A ships’ convoy in the area made an unsuccessful attempt at rescue. Her body was never recovered. Parts of the plane, her travelling bag, logbook and chequebook washed up later.

Speculation about her death has continued over the decades. There was a rumour of two bodies in the water, giving rise to the theory that she was on a secret mission. There was talk that she had been shot down by friendly fire (in essence, by the British, after not acknowledging call signals). Maybe she just got lost in the extreme weather conditions, ran out of fuel and had to ditch her plane.

The RAF Accident Record Card of the time lists Herne Bay as the location of Amy’s final flight.

The Amy Johnson Project commissioned the pictured statue from Ramsgate artist Stephen Melton to commemorate the 75th anniversary of her death in 2016. A second identical statue was cast for the city of Hull, her home town. Both bronzes carry her quotes.

Amy V. Johnson’s name is carved within the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede, Surrey, a memorial for those in the Air Force who were lost during the Second World War and who have no known grave.

Amy Johnson became a living legend after becoming the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia. Here we look at her extraordinary story.

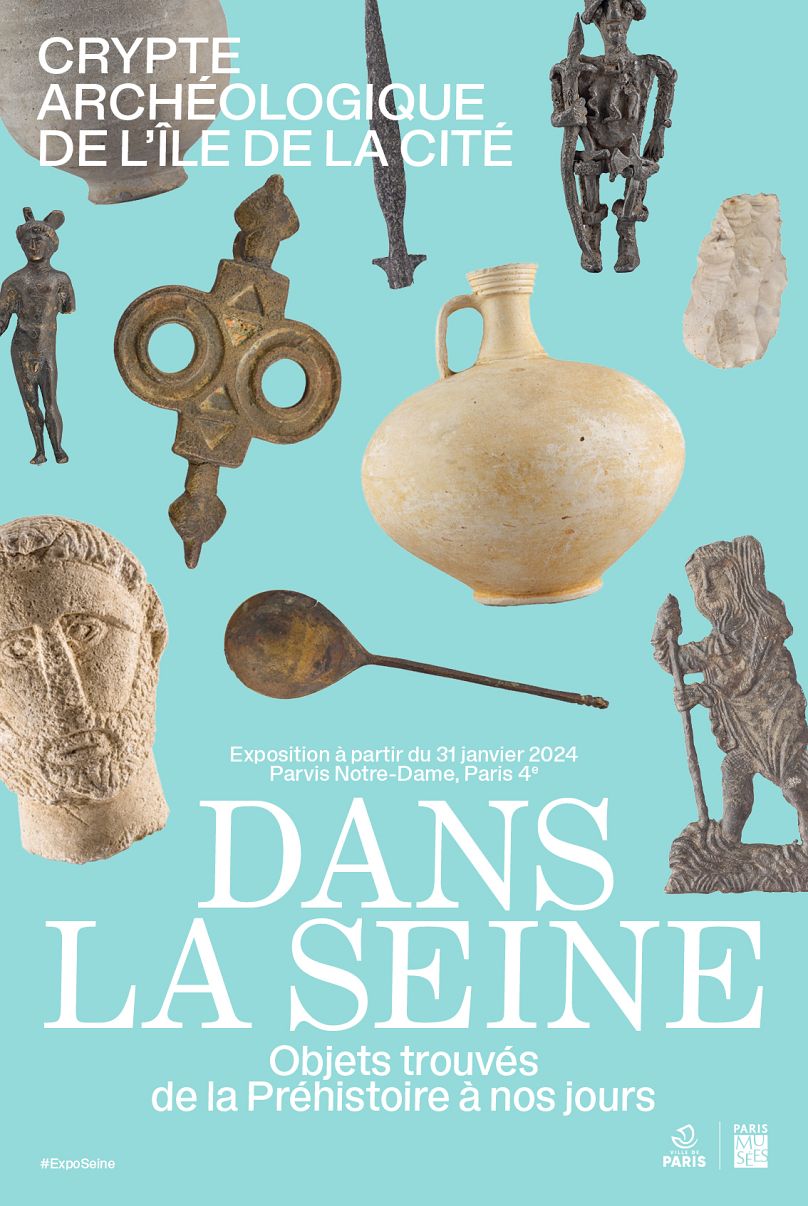

Beneath the tourist-packed plaza of Notre Dame Cathedral, an archaeological site tells the story of Paris and its River Seine through objects excavated from its bed and banks. Discover the exhibition “Dans La Seine”.

With Paris preparing to host the summer Olympics this year, the Seine has found its way back into the spotlight, as city officials scramble to get it clean enough for swimming before the competition begins.

But it’s not the first time the river has attracted this kind of attention. The major artery running through the City of Lights has forever been the star of the show, the very reason the city exists at all.

A new exhibition at the archaeological crypt underneath Notre Dame Cathedral explores the importance of the Seine to the people living near it, through objects that were excavated from its riverbed and banks.

The collection of 150 trinkets tells the story of how humans have interacted with the famous river, from prehistoric times to now. In doing so, it also tells the story of how Paris became Paris.

If you want to visit the exhibition “Dans La Seine,” you first need to find it.

Located underneath the plaza outside Notre Dame Cathedral, the Crypte Archéologique de l'Île de la Cité (archaeological crypt of Île de la Cité) was first discovered in the 1960s during the construction of an underground car park.

Today, it’s the only archaeological site open to the public in the entire city, but even many locals have no idea it exists. The understated entrance is just a stone’s throw away from the retractable seating packed with tourists looking at the cathedral – which is still undergoing renovation work after the 2019 fire.

Once you’ve found the entrance, climb down the stairs and you’ll find a sprawling excavation site spanning 1,800 square metres and packed with extraordinarily preserved archaeological rema

The site includes vestiges of a Gallo-Roman public bath, part of an old city wall and the docking port of the Gallo-Roman city of Lutetia, which is now present-day Paris.

The space is impressive on its own, but the temporary exhibition space presents a different way of looking at the history of Paris – a story told through the items found at the bottom of the River Seine.

As the main waterway snaking its way across the French capital, the Seine has seen more than its fair share of human paraphernalia hit its waters. Since the dawn of time, people have been dumping things into the river – both accidentally and on purpose.

These days, you’re likely to find electric scooters and rental bikes. But back before Paris was even an abstract concept, Neanderthals left flint tools on the Seine’s banks, evidence that they weren’t as primitive as scientists once thought.

Later, when the city on the Seine was known by the name Lutetia, residents of the Gallo-Roman outpost sometimes made offerings to the river in exchange for good fortune.

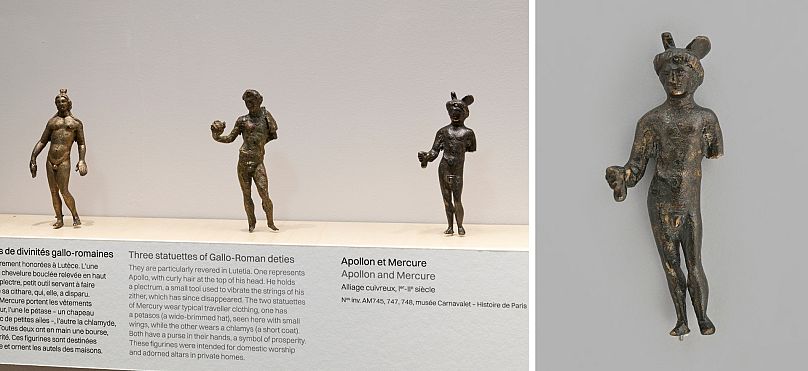

Once adorning altars in private homes in Lutetia, metal figurines of deities like Apollo and Mercury were found underneath layers of silt on the riverbed. There are several hypotheses for how they ended up there – they could have been stolen, dropped accidentally or made as an offering.

Mysticism around the Seine was prevalent for the Gallo-Romans – also on display at the exhibition are sculptures believed to be ex-votos, or votive offerings to the deity of the Seine, Sequana. Some 1,500 of these ex-votos were found near the river's source in Burgundy, where a temple was built to Sequana.

Made from stone, metal and wood, they depict animals, heads of men, women and children, full-length figures, swaddled babies and even body parts instructing the Goddess on where exactly she should apply her healing powers.

The cleaning and dredging of the Seine became routine maintenance for the city starting in the mid-19th century, a way of maintaining the river's depth so it would be easier to navigate. Objects were often discovered and removed when the sand and silt were extracted from the riverbed.

Objects found in the Seine from the Bronze Age and Middle Ages, after the fall of the Roman empire, include a huge collection of weapons – over 100 of them.

Some of these weapons – mostly battle axes and swords – are believed to have been thrown in the river on purpose, as part of a ritual at the end of battle.

Starting in the mid-19th century, small artefacts made from lead were found in their thousands in the Seine, becoming known as the “plombs de la Seine”.

They include tokens used for entries to towns and places of worship, religious figurines and even what are believed to be the first tin soldier children’s toys.

The brigade's divers have recovered objects including artwork, decorative elements from Paris bridges and technical equipment from ships.

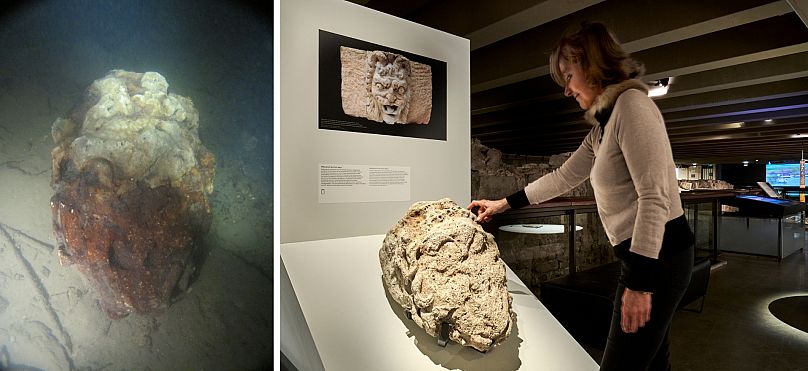

In 2014, they found a sculpture at the base of Pont Neuf that was identified as a mascaron, a stone molding in the shape of a mask that can often be seen on Paris buildings and monuments.

So what about us? What will our era leave behind in the Seine for future explorers to find?

Between the scooters, bicycles and motorbikes that have already been dredged up from the river and the debris that's sure to wash up during the Olympics, it doesn't look good.

But that's the nature of city rivers – they tell the story of the people who live around them, the good, the bad and the ugly.

The exhibition "Dans La Seine" is currently open to the public at the Archaeological crypt of Île de la Cité in Paris.